Bittersweet

The dying art of Mayan chocolate production

REPORTER

Ari Sen

PHOTO/VIDEO

Jeremiah Rhodes

Matthew Westmoreland

Dustin Duong

INTERACTIVE

Michael Gawlik

Nestled inside the lush green forest off the coast of Belize, dozens of green and red cacao pods grow.

Cacao has been cultivated here since 1800 B.C., when the Mayans first discovered they could turn these pods into a rich drink.

The pods start out as white flowers, smaller than a pinky finger, pollinated by insects so tiny they can hardly be seen with the human eye. After more than three years, these flowers grow into oblong pods roughly the size of cantaloupes. As soon as the pods start to show hints of gold, they are harvested with sticks or machetes.

The farmer, Narciso, plucks one off and breaks it in half, revealing the white seeds inside. These slimy wet beans look like something from an alien planet, but have a citrusy sweet flavor, more akin to an orange than a bar of chocolate.

Farming cacao is a seemingly never-ending process. Growers like Narciso harvest the pods once every 10 days for six months. In the off season, the groves require continual maintenance to stave off pests and disease and to make sure the pods are getting the optimal amount of shade — too much and the trees drown in moisture, too little they dry up and die.

After harvesting, Narciso’s brother, Julio Saqui, takes the beans from his brother’s farm and uses them to create fine chocolate.

Saqui’s storefront is a square concrete box, emblazoned with the brand name Che’il, the Mopan word for “wild.” The store’s walls are painted a verdant green, matching the flora outside, and the floors are a rich orange clay. Local art from village members sits on shelves next to a corner refrigerator, which holds the result of a 21-day process of plucking, fermenting, drying, roasting, crushing and grinding of the beans, wrapped in foil.

The cacao industry in Belize has always been precarious — subject to the whims of both tumultuous markets and the worsening climate. But to Saqui, chocolate is more than just a sweet to sell to the country’s many cruise ship tourists — it’s his way of life.

“Maya people look at cacao beans as medicine,” Saqui says. “Today the commercial world looks at chocolate as a treat.”

“What is it?”

Pedro Saqui had a feeling.

Government experts told him his citrus trees would be safe from the incurable Asian disease. But after a lifetime of farming, something told him he needed to take a different path before it was too late.

“My dad said, ‘We’re going to plant cacao,” Saqui said. “I said, ‘Cacao? What is it?’”

More than 20 years later, cacao and chocolate making consume his every waking minute.

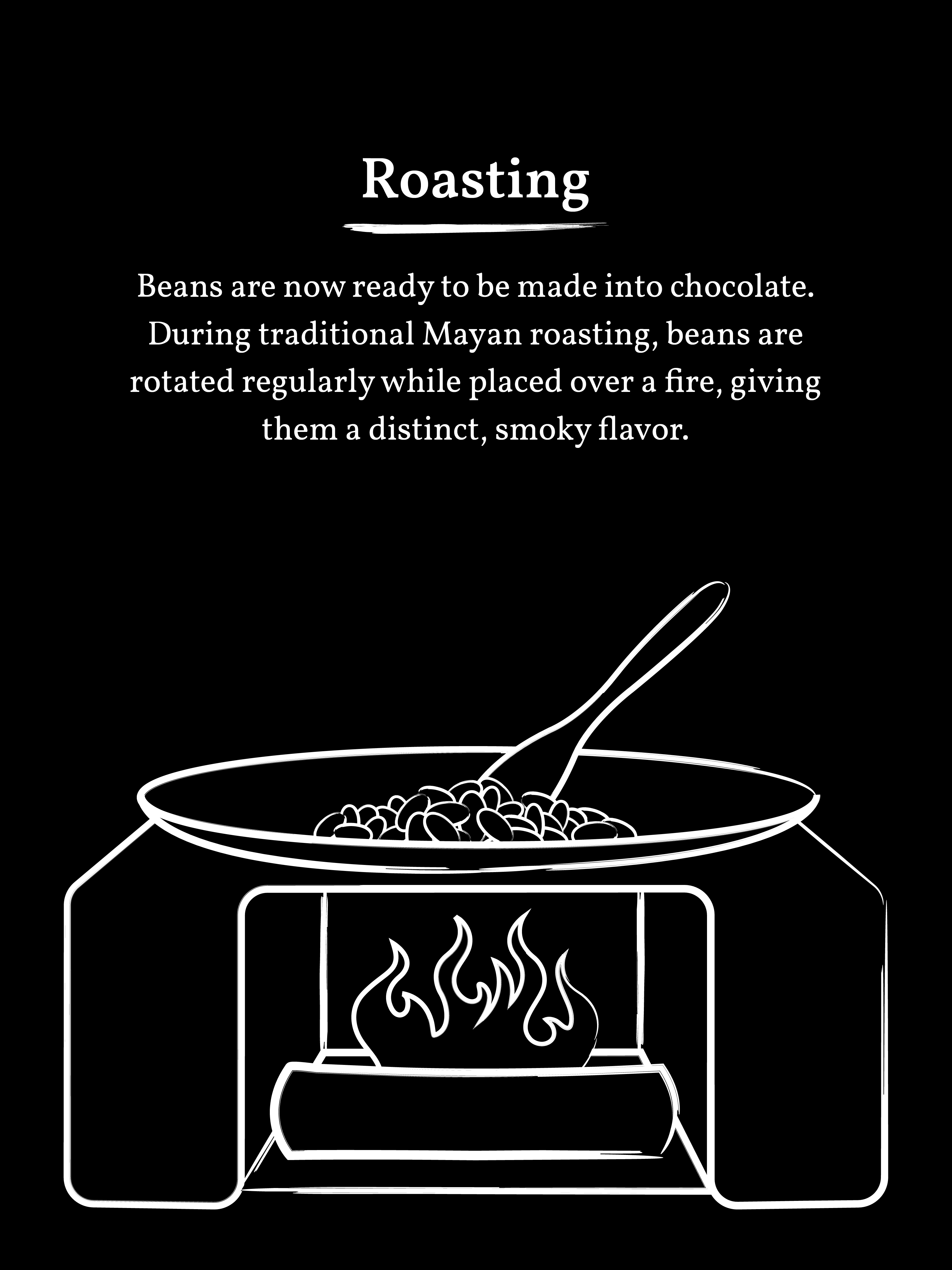

Saqui begins his process of chocolate making when he receives the organic wet beans from the small farms in the area, like the one his brother runs. He then pours them into wooden crates to ferment for six days. After going through the various stages of fermentation, they are put on shelves in a drying house for another seven days before being roasted.

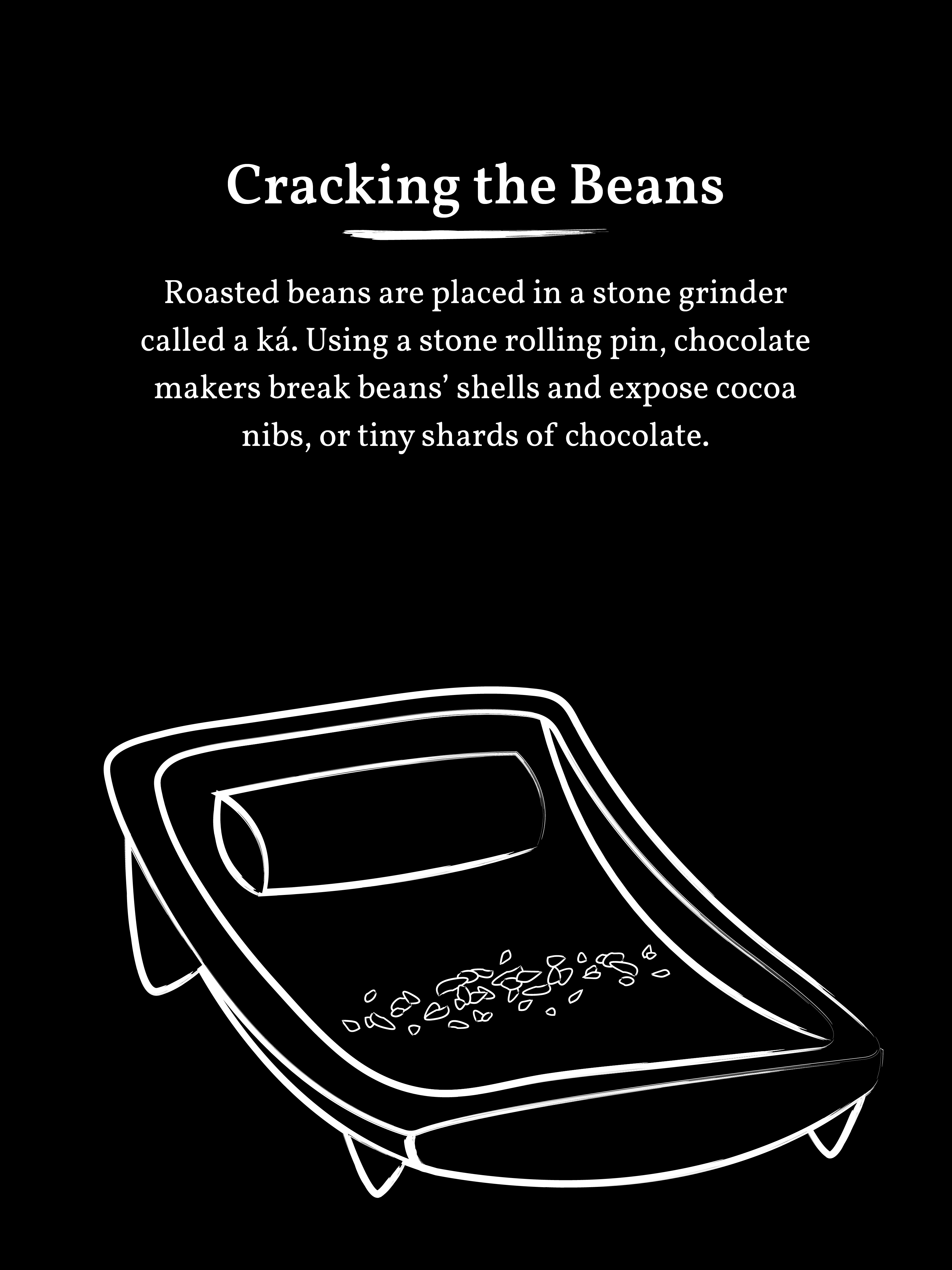

Even though it would be much easier to roast all of the dried beans in his machine, Saqui still mixes them with those roasted on a large clay plate over an open fire. The fire-roasted beans are then smashed by hand on a Ká, or traditional Mayan grinder, and combined with the beans crushed in a machine. The mixture is combined with varying levels of sugar and is spun in machines for hours.

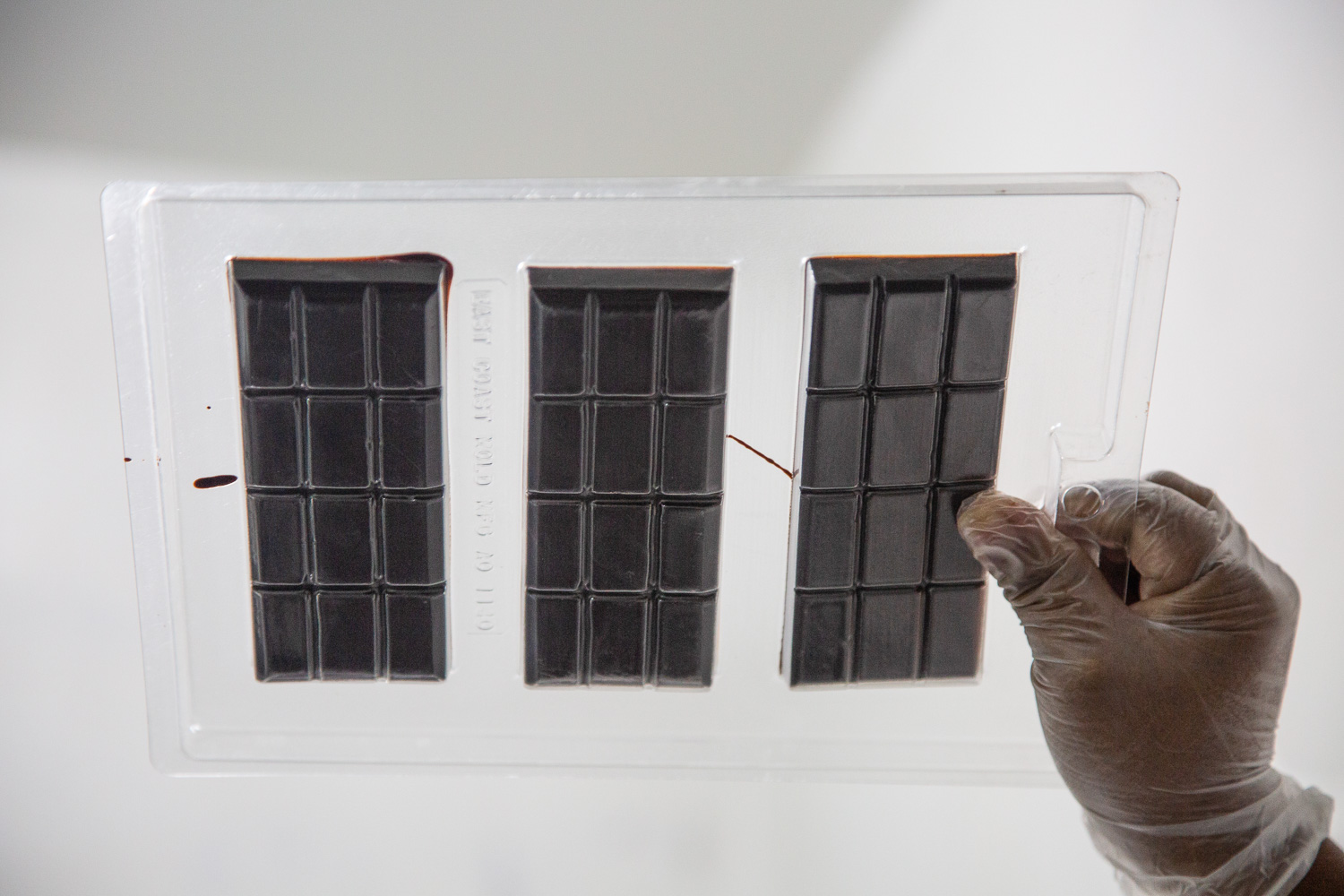

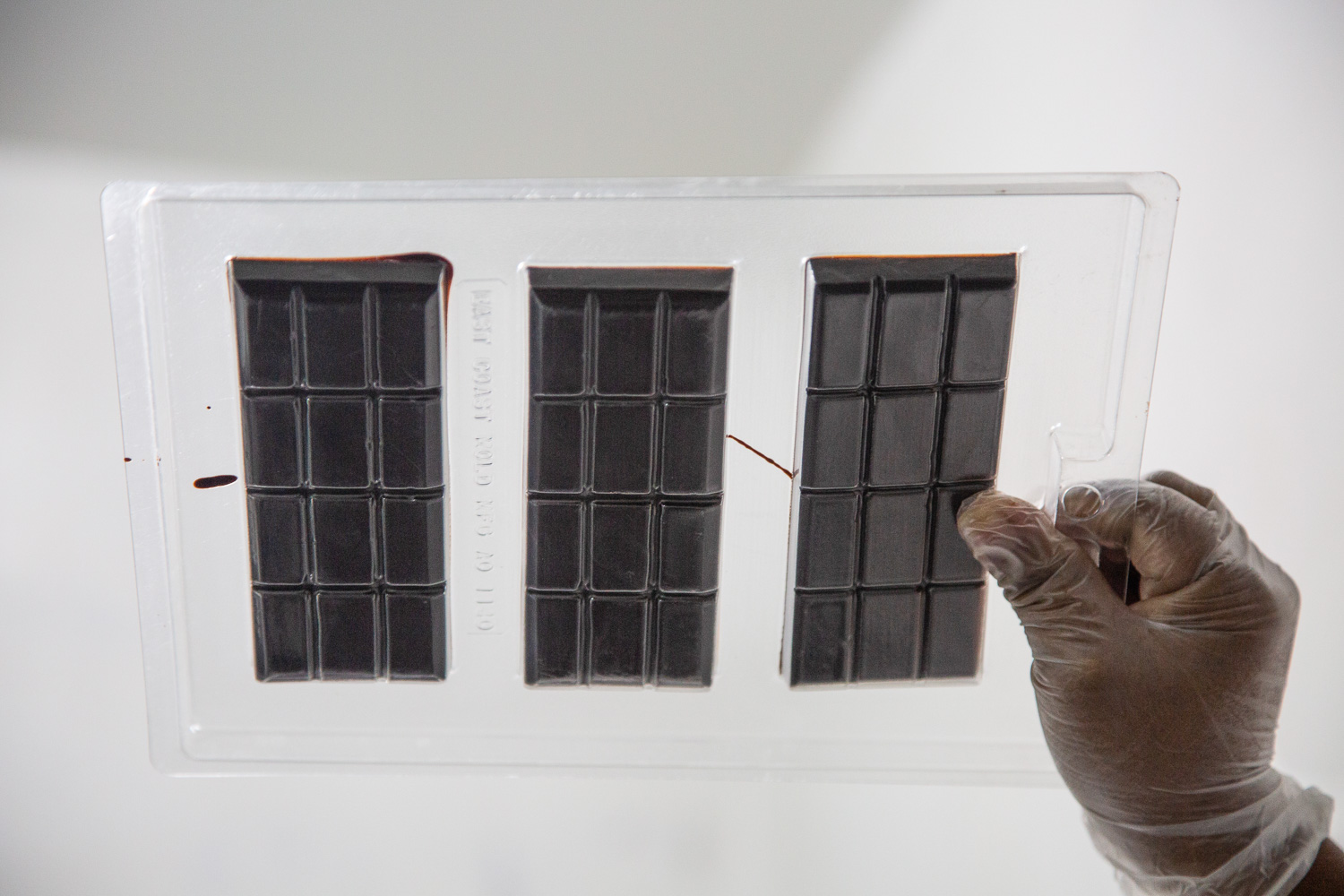

On piping days, Saqui frequently wakes up in the earliest hours of the morning, so he can distribute finished chocolate into plastic molds while the temperatures outside are relatively cool. As the sun begins to rise, he and his wife supervise a small staff who wrap the bars in foil.

Saqui uses a spatula to stir a plate of roasting dry cacao beans. These beans will later be grinded by hand and mixed with beans roasted in a machine in order to balance flavor and profitability. Photo by Ari Sen.

Saqui is one of only a handful of chocolate makers in Belize, of which only a few are locally owned. Unlike some other producers, his bars contain no additives or fillers.

“The first thing that people say when they bite our chocolate is ‘Wow, it’s rich,’” Saqui said. “When you taste those fillers, they have that chocolaty flavor, but the richness, the sweet aftertaste on your palette is just not there.”

“My training is not from school”

Saqui said his mother was the one who taught him how to roast cacao to turn it into a rich chocolate drink. It wouldn’t be until years later that he turned chocolate making into his full-time profession.

By the time he produced his first bar of chocolate, she was on her deathbed.

“My training is not from school — I learned my chocolate making from my mom,” Saqui said.

“I didn’t want her not to taste my chocolate before she passed.”

This type of cacao production has been a part of Mayan culture for centuries, passed down through generations. The plant holds a spiritual significance for Mayan people, Saqui said, and is used in rituals such as those marking momentous occasions like weddings.

More than 42,000 Mayan people live in Belize, or more than 11%of the country’s population. But even though Mayans represent a large percentage of the population — roughly the same percentage of black people who live in the U.S. — they have long struggled in territorial disputes with the Belizean government.

Under British occupation, Mayan people were not allowed to own land. Even to this day, 44% of all land in Belize is under protected area status, meaning it is either owned or administered by the government.

In 2015, after a nearly three-decade-long court battle against the government, a coalition of Mayans from the Toledo District were granted the right to 38 traditionally Q’eqchi and Mopan communities by Belize’s highest court.

But it isn’t just the government who has threatened Mayan lands. Saqui said Mayan cacao farmers are being driven out of the industry by large companies, forcing them to sell their land for pennies on the dollar.

“What the big farmers and buyers are doing is that they’re paying this farmer a very small amount of money so that he gets disappointed, he loses interest,” Saqui said. “The next best thing for him to do now is to sell his land to the bigger farmer or a buyer so that then that we can, they can harvest everything.”

A Catholic church sits on the side of the road a few miles outside the Toledo District in Belize. Saqui attributes the growth of churches and Christianity in the country to the decline in Mayan cultural practices. “I have a choice-- It's either I sell my soul and self to being a Christian, or being antichrist by practicing my own cultural form of living,” Saqui said. “I prefer my old culture, because that has taught me, that has grown me, that has made me a man.” Photo by Ari Sen.

With the loss of land, Saqui says, so too has gone much of the Mayan culture and religion he cherishes. Particularly at fault is the rise of Chrisitianity in the country, Saqui says. According to the latest census numbers, more than 74%, or over 300,000 Belizeans, practice some sort of Christianity.

“Inside the Bible, there is nowhere in there that the Maya culture exists,” Saqui said. “If we only live just the Bible life or the Christianity life, then what happens to my culture?

“The Heartbeat of the Industry”

The jungle road seems traversable by only the toughest of four-wheel drive systems, but Saqui doesn’t seem daunted. His brown Nissan Altima, which he calls his “little armadillo,” moves gracefully over the treacherous terrain, guiding itself deeper into the thick forest.

He is trailing behind a Ford pickup, carrying Jose Mess, 53, and his son Bradford Keith, picked up a short time earlier from their thatched-roof home a few miles away.

When the vehicles can go no further, the three men step out and begin a short march toward the grove of more than 200 cacao trees.

After crossing a stream the pods begin to emerge: green-yellow foresteros and deep burgundy trinitarios, which are sought after around the globe for their distinctive taste.

Even under the canopy of the madre de cacao shade trees, the air is hot and sticky. Hordes of mosquitoes buzz around, leaving countless red blotches on their victims’ flesh. Despite the heat and pests, the Messes travel to this grove constantly to prune infected pods, fill buckets with wet beans and hack off extraneous branches with their machetes.

Though much of the work remains the same, a lot has changed since Jose Mess began harvesting cacao 32 years ago.

Deforestation has forced birds and squirrels from fruit trees to cacao groves in order to find food.

Rising temperatures make these trees harder to grow and cause rain which can flood their roots.

The economics of the industry are also particularly perilous. Ever since Belize’s cacao market earnestly began in 1977, when The Hershey Company acquired several hundred acres in the central part of the country, it has been racked by instability for both farmers and processors.

Hershey entered Belize during a boom period — that year prices peaked at over $5,700 a ton. Over the next several years, the company expanded its reach in the country, and fostered the creation of new farms across the country. In the Toledo District alone, cacao farms increased from 237 acres in 1983 to more than a thousand at the turn of the decade. These farms, in turn, sold Hershey almost 32,000 pounds of cacao that year.

But as Hershey and other companies were developing their farms, the price of cacao began to drop. In 1993, the company exited Belize — the global price of cacao had plummeted more than 64% in nine years. (Representatives for Hershey did not respond to a request to comment on this story.)

In 1994, Green and Black’s, a British fine chocolate company, began purchasing beans from the country with the help of the Toledo Cacao Growers Association, a nonprofit created to improve the living standard of its members. In the next seven years, the association exported approximately 20 tons of cacao beans annually from more than 200 small farmers.

In 2001, Hurricane Iris destroyed more than 500 acres of cacao in the southern coastal districts of Belize, leaving the association and Green and Black’s to foot the bill to rehabilitate half of its member farms.

After a short period of low productivity, the Belizean cacao industry slowly began to bounce back. In 2003, the two organizations, along with the UK’s Department for International Development and a Dutch nonprofit organization, established the three-year-long “Maya Gold Program,” which more than tripled the association’s membership and increased production to an average of more than 30 tons annually.

With the project came more stability and better pay for farmers — association farmers were paid $1.15 Belizean per pound of wet beans, at least 40 cents higher than the rates today, according to Saqui.

In 2005, the chocolatier was acquired by Cadbury, which was then taken over by Kraft Foods (now Mondelez International) five years later. As the size of the company grew, the Cacao Growers Association struggled to keep up with demand. In 2017, the company announced it would sell a chocolate bar that was neither organic nor fairtrade, a shift away from the company’s founding values. (Mondelez and the Toledo Cacao Growers Association did not respond to requests for comment on this story.)

“I regret selling Green & Black’s to Cadbury,” one of the chocolatier’s co-founders, William Kendall, told The Telegraph in 2015. “It was a mistake. A great shame. I wish I’d kept hold of it.”

Saqui now says the Toledo Cacao Growers Association is a shell of its former self.

“When it pulled out of Belize, it not only took away Green and Black’s from the association, it took away basically everything — the heartbeat of the industry,” he said.

Paying for Poverty

Emily Stone, the founder and CEO of Berkeley-based Uncommon Cacao, said that even though Green and Black’s provided stable income for small farmers, it did not have their best interests in mind.

After hearing about the issues facing Belizean cacao industry from a friend in the industry, Stone quit her job at a Boston-based environmental capital management firm to start Maya Mountain Cacao.

“I was like, ‘sign me up’ and I quit my job that day,” Stone said. “Two weeks later I was on a plane to Belize.”

In less than 10 years, Stone has grown the company to one of the largest in Belize. Less than two weeks before Belize reported its first case of COVID-19, Maya Mountain General Manager Roxanna Chen said the company planned to source 65 metric tons of cacao beans this year, up from 47 in 2019.

Both Che’il and Maya Mountain purchase most of their beans wet and complete the drying process themselves, rather than leaving it up to the farmers. Though Che’il is much smaller than Maya Mountain, Saqui pays his farmers seven-and-a-half cents more per pound of these wet beans than Maya Mountain.

Cacao pods lay cracked open, exposing the pulp-covered beans inside, during Narciso Saqui’s harvest on his farm in Kendal, Belize, on March 11, 2020. Photo by Dustin Duong.

Demand for fine cocoa products, like the so-called “bean-to-bar” variety Maya Mountain produces, has exploded in the U.S. in recent years. Sales of premium chocolate grew 19% in 2018, according to the Fine Chocolate Industry Association, compared to 0.6% growth in the mainstream chocolate industry.

To keep up with demand, Stone now operates or works with cacao buyers in Guatemala, Honduras, Haiti, Colombia, Ghana and Uganda as part of Uncommon Cacao, an organization that connects producers to the global chocolate market.

Despite the increased demand abroad, profits haven’t seemed to trickle down to small Belizean farmers. For their hours of toil, cacao farmers in the Toledo District only earn an average of $4,392 a year, according to 2015 Maya Mountain calculations. Only about 15% of this revenue comes directly from cacao. Most farmers are forced to supplement their income by growing other crops such as maize or bananas, or by offering tours to outsiders.

Stone says one of the primary reasons why so many farmers live in poverty is because large companies like Hershey treat cacao as a geographically — neutral commodity, not the result of hours of labor.

“When we pay less than $2 for a chocolate bar, we are paying for the systemic poverty of millions of families,” Stone said during a July 2017 presentation at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Saqui holds up three chocolate bars which have begun to separate from their molds after cooling. He often wakes up at 4 a.m. to make sure that he can pipe and wrap the bars before the mid-day heat begins to melt the chocolate. Photo by Ari Sen.

This level of poverty is not unique to cacao farmers in Belize. More than 40% of Belizeans live below the poverty line according to the World Bank. 13.9% of the country makes less than $2 a day. But unlike with other industries or crops, the Belizean government does not currently subsidize cacao farmers or producers, Stone said.

Some organizations like Ya’axché Conservation Trust, a non-governmental organization which works with communities and farmers to promote more sustainable practices, are trying to change that. Community Liaison Manager Julio Chub said the cooperative is currently working with the Belizean forestry service to expand land access to cacao producers.

“I believe what we’re trying to do here at Ya’axché is to influence the country of Belize through developing agroforestry policy that will guide or protect the rights of farmers and take into consideration the income-generating agriculture alternatives,” Chub added.

Saqui said that although he would appreciate more help from the government, it doesn’t have the know-how to provide proper support for the problems that face cacao growers in the future.

“The cacao industry in Belize is still very much a new industry,” Saqui said. “It is young, and it is still starting — there is a high level of uncertainty.”

More from Barriers